BLOG

Calabria’s Revival: Ancient Roots, Modern Ambition

Andrea Eby

Regions and Producers

Calabria, the rugged southern tip of Italy’s boot, is a region where ancient history and modern revival intertwine in compelling ways. Though long overshadowed by more famous Italian wine regions, Calabria possesses one of the most storied viticultural lineages on the peninsula. Over millennia, Calabria’s fortunes have risen and fallen, yet today a new generation of producers is bringing this historic region back into the spotlight, crafting wines that express both their deep roots and their contemporary aspirations.

Ancient Roots, Modern Revival

When Greek settlers arrived in the 8th century BCE, they found a land rich in vineyards and named the region Oenotria. They called its people the Italoi, a term that would eventually give rise to the name “Italy.” Cities like Sybaris, Krotos, and Rhegion flourished as commercial hubs enriched by fertile plains and Mediterranean trade. Such was the city’s reputation for lavish living that the term “sybaritic” endures as a synonym for indulgence. Such was the value of viticulture that vineyard plots reportedly fetched prices six times higher than other agricultural land.

This prosperity proved temporary. Over-cultivation and poor land management led to soil exhaustion and Roman shifts toward cereal cultivation further weakened the once-flourishing wine industry. Following the fall of Rome, Calabria endured centuries of political turmoil that only ended with the unification of Italy in 1861. While unification brought political alignment, it resulted in further economic disparity. Calabria remained isolated and increasingly plagued with crumbling infrastructure and limited access to export markets. Waves of emigration only served to exasperate the issues. As ports deteriorated and trade routes shifted, Calabria's wine industry contracted, and the region entered a prolonged period of economic decline.

The 20th century brought additional challenges. The 'Ndrangheta, one of the world's most powerful criminal organizations, stifled outside investment and contributed to economic instability. Many vineyards were abandoned. EU vine-pull schemes in the 1990s resulted in a 70% decline in vineyard acreage within a decade. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, what wine Calabria did produce went largely into vino da taglio, deeply colored, high-alcohol blends used to fortify lighter northern wines.

A turning point came in the mid-20th century with agrarian reforms led by Fausto Gullo. By dismantling the old latifundia system and redistributing land to small farmers, he laid the foundation for Calabria’s current landscape of family-run estates—a structure that remains defining today.

Geography and Climate

Over 90% of Calabria consists of hills or mountains with narrow plains pressed between land and sea. The Mediterranean climate brings hot, dry summers, tempered by proximity to the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas. Tramontane and Sirocco winds sweep through vineyards, reducing disease pressure and moderating heat stress.

Soils vary dramatically: sandy marine gravels, limestone outcroppings, clay-rich hillsides, and alluvial plains. Each soil type produces distinct expressions of the region's native grapes. Drought remains a persistent challenge, intensified by climate change, but Calabria's indigenous varieties have adapted to water scarcity over millennia.

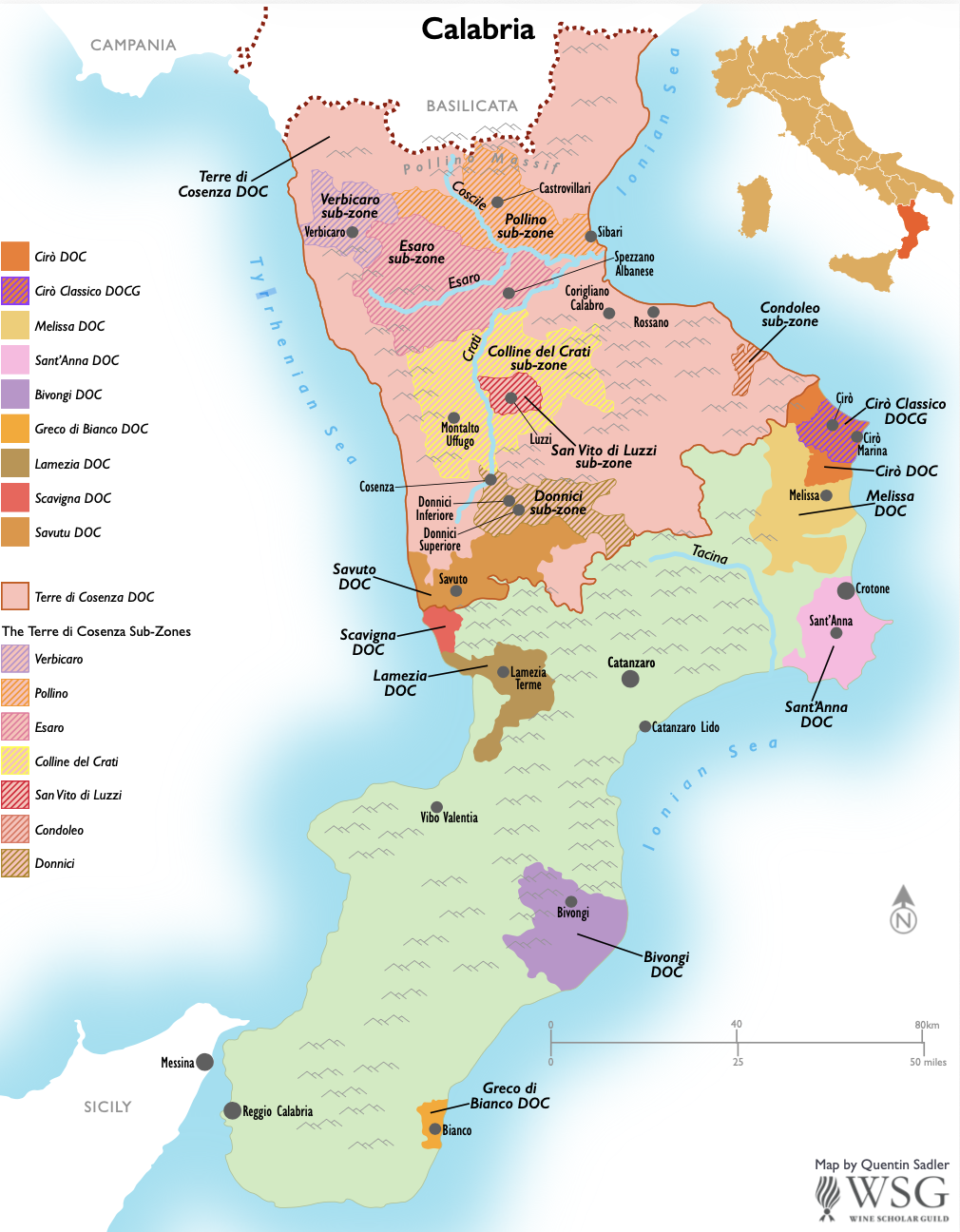

Today the region produces 250,000–300,000 hectoliters annually, approximately 70–75% red. Only about 12% qualifies as DOC or DOCG. The scale remains small, but quality-focused producers are redefining what Calabrian wine can be.

Cirò: Ancient Vineyards, Modern Tensions

Calabria’s movement away from bulk production toward authenticity and higher-quality wines is anchored in Cirò, one of the country’s oldest continuously cultivated viticultural areas.

Krimisa

One of the most famous wines produced in Calabria during the Greek period was Krimisa. Krimisa was “the” wine given as a reward to the winners of the ancient Olympic Games. The name Krimisa is believed to derive from the ancient Greek colony, Cremissa. It corresponds to the modern-day town of Cirò Marina.

Cirò is both a geographic and cultural center of Calabrian wine. The appellation encompasses two distinct settlements: the historic hill town of Cirò and the coastal village of Cirò Marina, situated along the central Ionian coast within the province of Crotone. This dual character reflects centuries of settlement shaped by geography and shifting socio-political forces.

Throughout the medieval and early modern periods, Cirò remained largely feudal in structure, with most inhabitants living in the defensive hilltop settlement of Cirò town. Following agrarian reforms after World War II, driven in part by the dismantling of the feudal latifundia system, many families relocated from the crowded hilltop to the more accessible and healthier coastal plain around Cirò Marina. This migration reshaped not only settlement patterns but also vineyard distribution and management practices.

Awarded DOC status in 1969, Cirò is Calabria's oldest and largest appellation by volume. The production zone extends from the coastal town of Cirò Marina inland to the hills surrounding Cirò, positioned between the Ionian Sea and the foothills of the Sila mountain range. The appellation covers approximately 1,500 hectares of vineyards, with roughly 500 hectares falling within the Classico subzone that encompasses the traditional hillside vineyards around both settlements. As of 2024, the region produced about 4 million bottles annually from approximately 65 wineries and 300 growers.

The vineyards occupy a distinctive transitional landscape—coastal plains give way to hillsides that rise toward the Sila massif. Maritime breezes from the Ionian Sea moderate summer heat, while the Tramontane and Sirocco winds sweep through the vineyards, reducing disease pressure and maintaining cluster health. Elevation varies significantly across the zone, creating diverse mesoclimates. Soils consist primarily of sandy gravels and clays of marine origin on the hillsides, offering excellent drainage and moderate fertility that encourages deep root development.

The Cirò Revolution: A Movement Defines a Region

In 1996, the original Cirò DOC regulations were amended to permit international varieties in the blend. Larger wineries embraced the flexibility, viewing it as a path to broader market appeal. But a group of small producers saw it differently, they believed Cirò's future lay not in adaptation to international tastes, but in pure expressions of Gaglioppo. In an era when oak aging was increasingly fashionable, these producers rejected the use of barriques and instead aimed to produce 100% Gaglioppo wines whose expression of terroir was unobscured by flavours of oak.

This philosophical divide gave birth to the Cirò Revolution, spearheaded by producers including Sergio Arcuri, A' Vita, and Tenuta del Conte. The movement's members committed to a strict set of principles: 100% Gaglioppo, no barriques, minimal intervention, and wines that express Cirò's essence rather than conforming to international templates. Their logo—a fist gripping pruning shears—captures the movement's defiant spirit.

The Revolution redefined what Cirò could be, and in doing so, opened the door for other Calabrian regions to reassert their own identities.

Gaglioppo: The Grape Behind Calabria’s Wine Renaissance

Gaglioppo is Calabria's signature red grape, found in nearly every DOC except Greco di Bianco. Despite its thin skins, the variety produces wines of considerable structure—high acidity, robust tannins, and an aromatic profile of roses, violets, wisteria, spice, and tobacco. Its pale garnet color with orange tinges often draws comparisons to Nebbiolo; however, stylistically it has the potential, in the right hands, to deliver the aromatic complexity of Barolo and the savoury earthiness of Brunello. The comparisons to Brunello are not unfounded, as genetically, Gaglioppo descends from Sangiovese, likely through a natural crossing with Mantonico. In the winery, Gaglioppo behaves much like Sangiovese. Both varieties lack acylated anthocyanins, making their color less stable and more prone to oxidation. If harvested even slightly underripe, Gaglioppo's tannins can remain coarse and unpolymerized. Ferment too hot and oxidation accelerates. Handle it gently and the wines can be notably perfumed, with considerable aging potential.

Like Sangiovese and Nebbiolo, Gaglioppo has the ability to clearly transmit terroir in the glass. Clay-limestone hillsides often yield fragrant, structured wines; sandy soils create lighter and more saline expressions, while alluvial zones produce rounder, spicier renditions. Regardless of soil type, the wines often show dried fruit, leather, savory herbs, and spice even when aged in concrete or steel. Its aromatic depth and firm tannins give Gaglioppo the capacity to age well and improve with extended cellaring.

The DOCG Debate

Nearly three decades after the Cirò Revolution began, the philosophical tension it represented has resurfaced with the 2025 elevation of Cirò Classico to DOCG status—Calabria's first. The designation applies exclusively to red wines from the historic Classico subzone and mandates stricter production standards: a minimum 90% Gaglioppo (though most producers will use 100%) and 36 months of aging including at least 6 months in wood. On paper, the DOCG aims to elevate quality and typicity from vineyards long considered the source of Cirò's most structured wines.

In practice, the wood-aging requirement has sparked considerable debate. In a recent conversation, Calabrian wine expert Giusy Andreacchio cautioned that the DOCG risks alienating the very producers who restored Cirò's reputation: "Many of the new-wave winemakers don't use oak at all. Gaglioppo's generous tannins provide plenty of structure to the wines. Aging in oak only serves to intensify these tannic elements. Mandating the use of oak goes against the very philosophy of the Cirò Revolution. Time will tell how many producers decide to bottle their wines as DOCG.”

Beyond Cirò

Calabria's complexity extends well beyond Cirò, supported by a range of terroirs and native varieties. Among its whites, Greco Bianco stands out as one of the region’s most compelling expressions. Calabria's Greco Bianco—genetically identical to Malvasia di Lipari—is at its most extraordinary in the Greco di Bianco DOC. Here, on the near tip of Italy’s toe, grapes are dried on racks in the sun to produce golden passito wines with aromas of orange blossom, honey, dried apricot, tropical fruit, and resin. Dry versions show crisp acidity and aromatic lift. Despite its name, suggesting a connection to Greece, there is essentially no genetic evidence to support this theory. The picture is further complicated by the fact that several unrelated Calabrian white varieties have historically been referred to as Greco Bianco, a catch-all name long applied to local white grapes.

Magliocco: The Next Calabrian Classic?

Magliocco—present primarily as Magliocco Canino and Magliocco Dolce—is one of Calabria’s most important native red varieties. Long thought to comprise numerous distinct grapes, DNA analysis has confirmed that only these two Maglioccos exist, clarifying a nomenclature that had been muddied by local synonyms and mixed plantings. The variety is known for its adaptability and its capacity to produce deeply coloured, structured wines with flavours of black cherry, boysenberry, dried herbs, oregano, and tobacco. Although well suited to Calabria’s warm Mediterranean climate, Magliocco is sensitive to drought, making site selection and yield management critical.

Magliocco Canino is the more widely planted of the two, especially in the provinces of Catanzaro and Cosenza, where it is typically used in blends to contribute colour, body, and tannin—often alongside Gaglioppo and Nerello Cappuccio. Magliocco Dolce, by contrast, is generally regarded as the higher-quality biotype. Despite not yet being formally listed in the Italian National Registry of Grapes, it is increasingly bottled as a varietal wine, with Librandi’s Magno Megonio offering a notable benchmark for the style. Because Magliocco Dolce is cultivated under multiple local synonyms and frequently interplanted with other varieties, it is believed to be the more widespread of the two. As producers continue to isolate and vinify it separately, Magliocco Dolce is emerging as one of Calabria’s most compelling native grapes, capable of delivering both concentration and refinement.

A Patchwork of Distinct Appellations

While Cirò and Greco di Bianco are Calabria’s best-known appellations, the region’s future also lies in the diversity of its smaller DOCs.

In the north, the Terre di Cosenza DOC stands out for its breadth and potential. This expansive appellation encompasses a wide range of elevations and soils, from the cooler foothills of the Pollino massif to the warmer coastal zones near the Tyrrhenian Sea. Here, Magliocco (particularly Magliocco Dolce) and Gaglioppo take the lead, yielding wines that range from fresh and aromatic to dense and structured. Subzones such as Donnici, Verbicaro, and Pollino continue to express distinct local traditions within the DOC framework.

Further south along the Ionian coast, Melissa DOC produces reds and rosés based on Gaglioppo, alongside a smaller proportion of white wines. The wines often show a balance of ripeness and freshness shaped by maritime influences. Nearby, the Bivongi DOC,one of Calabria’s smallest appellations, preserves a historical blend of Gaglioppo, Nerello Cappuccio, Greco Nero, and white varieties such as Greco Bianco and Ansonica, producing lighter-bodied wines with notable herbal complexity.

On the Tyrrhenian side, Savuto DOC draws on steep, terraced vineyards perched over the river valley that gives the zone its name. Its blends, typically incorporating Gaglioppo, Magliocco Canino, Aglianico, and Greco Nero, offer structure, spice, and a distinctive mineral thread. Lamezia DOC, located further south, produces a full range of wine styles—red, white, rosé, and even sparkling—often blending native varieties with small, permitted proportions of international grapes. Scavigna DOC, though small and less widely known, yields characterful wines shaped by calcareous soils and higher elevations.

This diversity is central to Calabria’s ongoing development. As producers articulate the expressions of their respective zones, the region’s identity is expanding beyond Cirò and revealing a more nuanced wine landscape.

A Region Repositioned

Despite labour shortages, climate challenges, and the lingering effects of economic disparity, Calabria is undergoing a measurable transformation. Producers are increasingly committed to native grapes, careful vineyard management, and quality-focused production rather than high-volume output. Wines that once disappeared into anonymous blending tanks are now celebrated for their authenticity and sense of place.

Calabria’s most compelling wines do not attempt to emulate international styles; their strength lies in tasting unmistakably Calabrian, shaped by native varieties, the region’s geography, and long-standing local traditions. As the DOCs across the region more clearly articulate their identities, they broaden the understanding of Calabrian wine and signal a shift in how the region is perceived. After decades on the periphery, Calabria is moving into the spotlight, its appellations increasingly acknowledged as important contributors to Italy’s contemporary wine landscape.