BLOG

Premiers Crus in Beaujolais: Cure or Curse?

Natasha Hughes MW

Regional Spotlight

On the surface, promoting Beaujolais’s best vineyards to premiers crus might appear entirely beneficial for the region. But the situation is more complex than it looks, says Beaujolais expert Natasha Hughes MW.

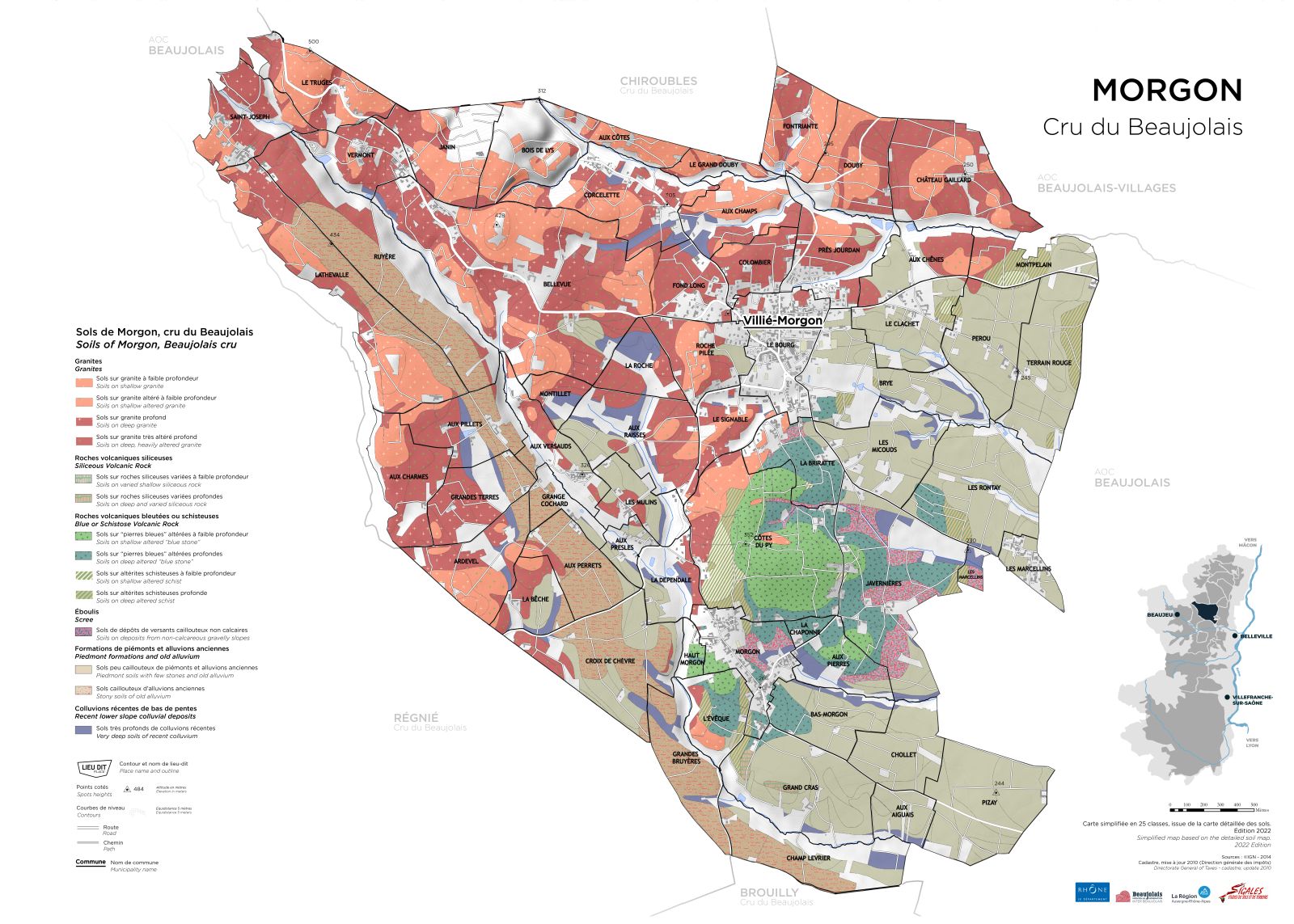

In 2024, Fleurie filed a dossier filled with evidence to support the elevation of a number of its lieux-dits to premier cru status. The crus of Moulin-à-Vent and Brouilly were quick to follow suit, and the Côte de Brouilly, Juliénas and Morgon may not be far behind.

These applications have been in the offing for quite a while now. I can’t remember when I first got wind of the fact that some crus were seeking official recognition for some of their best sites, but I do remember thinking that the notion was a sound one. The elevation of a small number of lieux-dits to a status associated with both prestige and premium prices seemed like a slam dunk for a region whose reputation has–undeservedly–languished in the doldrums. It came as a bit of a shock, therefore, to discover while researching my book on Beaujolais and its wines that not everyone believes that the creation of premiers crus is a desirable goal.

If I had to guess, my assumption would be that most of the people reading this article might find this revelation almost as surprising as I did. And yet, the more I listened to the arguments for and against the drive to create a formal hierarchy within Beaujolais’s crus, the more ambivalent I too became about the project.

Levelling up

To anyone who has undergone formal wine education, the arguments in favor of having premiers crus in a region seem obvious. To begin with, the mere fact that Beaujolais has premiers crus serves as a reminder to wine lovers everywhere that the region has some truly world-class terroirs.

Labels bearing the words ‘premier cru’ might also permit producers to charge more for these wines. This might not be an unalloyed benefit for the end consumer, but in a region where most winemakers are struggling to make ends meet, a couple of euros more per bottle might make all the difference between staying afloat and succumbing to the financial tide. When you bear in mind the labor involved in tending old bush vines planted at high densities on steep hillsides, it’s hard to begrudge producers a small price increase that might see the retail value of a bottle rising from around $35/£25 (a rough average for a Beaujolais cru) to, say, $40/£30.

That extra profit margin might, in turn, not only help to ensure financial viability for a Beaujolais producer, it could potentially allow for greater investment in the region’s vineyards and cellars. In the long term, this could result in the creation of even better wines, further reinforcing the virtuous circle between the purchase price and the sheer pleasure afforded by the liquid in the bottle.

And then there’s the issue of competitive advantage. Imagine, for instance, that you are based in Chiroubles and that you and your fellow growers have decided not to apply for premier cru status for any of your lieux-dits. Your competitors in neighboring Fleurie, on the other hand, have done so and–eventually (these things take a long time)–some of their vineyards have become premiers crus. When a wine lover in a restaurant–or browsing the shelves in their local wine shop–spots two bottles of Beaujolais side by side, and one is labelled ‘premier cru’ while the other is not, it doesn’t take a marketing genius to recognize that most people will assume that the Fleurie is the better wine. In other words, if one cru acquires the right to label some of its wines as premiers crus, it would be commercially unwise for other crus not to follow suit.

Structural damage

On the other hand, price increases don’t automatically follow on from the existence of premiers crus. Not all producers in the Mâconnais have benefitted from better financial returns since a number of their lieux-dits became premiers crus. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that the awarding of premier cru status to some vineyards has, instead, served to depress prices for many of the ‘regular’ bottlings from generic appellations within the Mâconnais.

Nor does it necessarily follow that a wine labelled as premier cru will automatically be of better quality than a wine without that designation. Many wine lovers are familiar with the notion that there are producers in the Côte d’Or–and elsewhere in Burgundy–whose Village-level wines are far superior in quality to premiers crus from lesser producers. This, in turn, begs the question of the real value of any such classification system–an issue cited by many producers in Beaujolais, who do not feel that they need an externally endorsed hierarchy to prove the quality and character of their terroir.

Local pride also plays a part in another objection. For many of Beaujolais’s growers the notion that their region has anything in common with their grander northern neighbor is not one that finds much favor. Although Beaujolais is officially part of greater Burgundy, many producers highlight the differences in culture, landscape, social history and terroir between the two regions rather than the similarities. For these vignerons, premiers crus belong to Burgundy and have nothing to do with the values of their own region.

The fiercely egalitarian spirit that is such a hallmark of the Beaujolais character is another factor that undermines the attraction of premiers crus. In a region that has had to learn the hard way that everyone needs to pull together to promote their wines, the creation of a notional quality barrier that raises one former neighbor above another lacks appeal.

There’s one final argument against the creation of premiers crus in Beaujolais (one that I would argue, has broad relevance elsewhere). The INAO (the French governing body that decides on whether or not premier cru status is awarded) insists on a glorious historical record of market demand and critical praise for the lieu-dit that is being elevated. As a result, undue emphasis is placed on vineyards that were capable of consistently ripening fruit in an era when many wines were routinely chaptalized. Typically, these sites are the sunniest and best-exposed vineyards in a cru. In an era of climate change and rising alcohol levels, these plots may not turn out to be the region’s best in years to come.

Brave new world

Some of the arguments cited above may resonate more or less strongly for you. I certainly feel that some of them deserve to be taken more seriously than others, and that work-around solutions can be found to many of the problems outlined here. Either way, it seems likely that premiers crus are coming to Beaujolais, whether or not the idea finds favor with us (or with individual producers in the region, for that matter).

The true challenge will lie in ensuring that the criteria on which the lieux-dits are selected, the qualitative constraints imposed upon them, and the way in which producers use their eventual premier cru status, are all truly relevant to enhancing the image of Beaujolais in the future.

Natasha Hughes MW’s book, The wines of Beaujolais, is published by the Académie du Vin Library on 22 September, 2025 in the UK and 1 November elsewhere. Available via this link - https://academieduvinlibrary.com/products/the-wines-of-beaujolais