BLOG

Marsala Wine 101: Why This Sicilian Fortified Wine Deserves Your Attention

Abbie Bennington

Regions and Producers

Marsala, the fortified wine hailing from the sun-soaked hills of Sicily. A wine that embodies the rich tapestry of history and culture of an Island just a stone’s throw from mainland Italy. Having recently returned from visiting the region here is a brief introduction and exploration of one of the world’s most underrated wines.

Marsala and Florio Wine Cellars

Marsala was one of the earliest wines to be awarded DOC status after Etna in 1969. The popularity of Marsala has waxed and waned over the centuries, but one producer remains fiercely in vogue, and that is Cantine Florio.

Florio Wine Cellars, located in Marsala, Sicily, is one of the most historically significant wineries in the world of fortified wines. Founded in the early 19th century by the Florio family, the cellars have played a crucial role in the production and global recognition of the eponymous wine.

The Florio family's journey into winemaking began in 1833 when Vincenzo Florio, a prominent Italian entrepreneur, and his brothers established the company. The Florios recognized the potential of Marsala. The wine was gaining popularity, thanks to English businessman John Woodhouse. He realized the potential of Marsala for British consumers already obsessed with the wines of Port and Madeira. Florio, therefore, set out to create a high-quality fortified wine that could compete in international markets.

Stepping across the threshold of Florio’s famous cellars on the western tip of Sicily was like turning back 200 years. The look, smell and feel of the cool dark eaves are evocative, a word often overused, but not here. Moving out of the white light of the glaring Sicilian sunshine into the soft warm brown of the cellars, you’re embraced by the heady aromas of dried fruit, oak and history.

A giant oak foudre holding 62 thousand litres of Marsala greets visitors on entering the cellar. It appears like a huge sentry guard, standing proud and immovable since the nineteenth century. Behind it, over three thousand barrels lie dormant, stretching out across 44 thousand square metres. Impressive, until you learn that these hallowed cellars once reached over 150 thousand square metres in Florio’s heyday.

How Marsala is made

Grapes are brought to Florio and pressed whole cluster, seeds, stems and fruit. In this way they aim to capture the ‘soul’ of the Grillo variety and the tannins, which help allow the wines to age. Here at Florio, only Grillo is used, however other varieties are legally available for wider Marsala production including Catarratto, Inzolia and Damaschino.

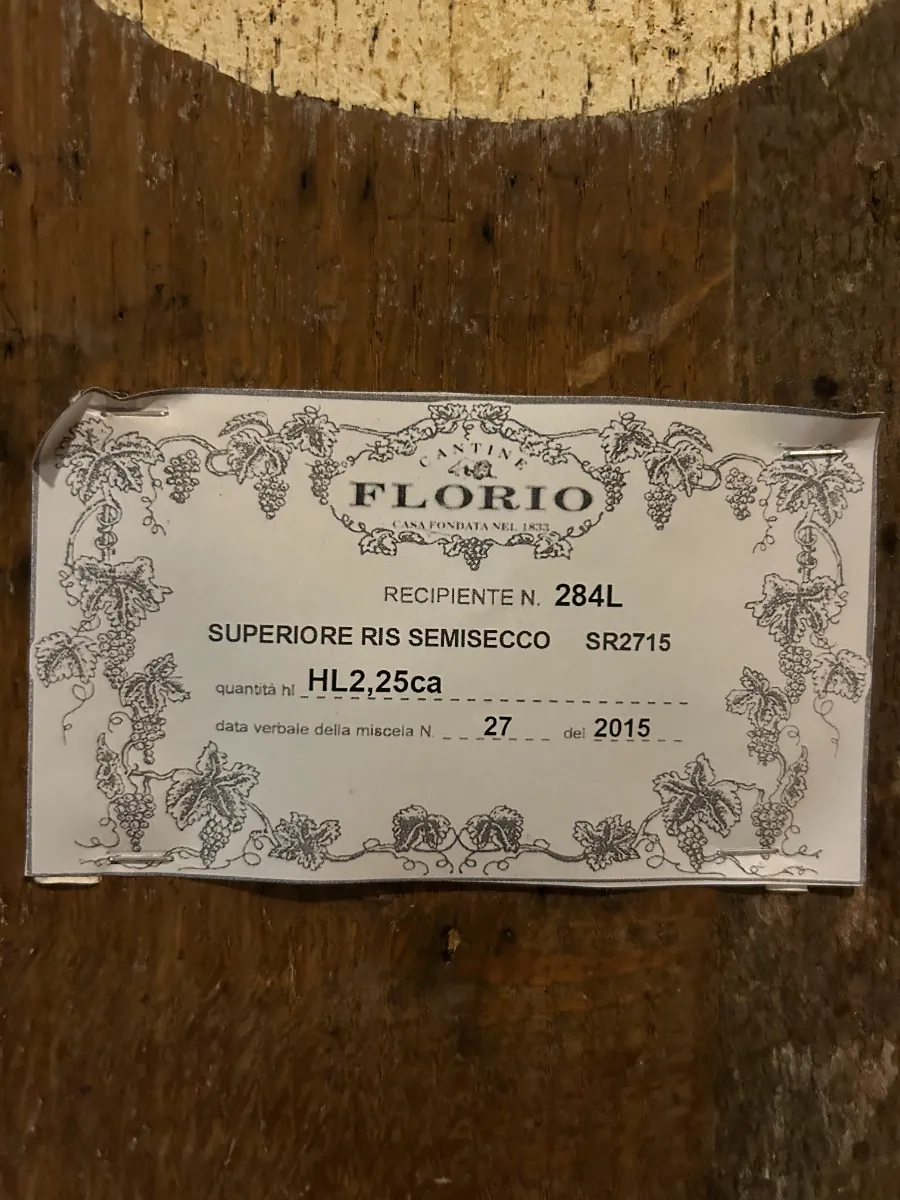

In the cellars closest to the sea, just 95 metres from the shore, the floor is wet, the environment humid and mold can be seen on the walls. As you move further inward, the cellar spreads across four aisles and the temperature starts to rise. This means that the positioning of the barrels, either closer to or further from the shore, will age and taste very differently. Every barrel is unique in its maturity and composition, and each will produce a singular stand-alone wine. The vintage stated on the label of the barrels refers to the date of fortification rather than that of harvest.

“Temperature is an important tool, we can use the same blend at one end of the cellar (and another) at the other, but a completely different Marsala wine will be created,” says oenologist for more than a quarter of a century here at Florio, Tommaso Maggio.

An enigmatic figure, Tommaso act’s part curator, part king of Marsala and rightly so. He is attuned to each barrel, testing them at random. He uses the stopper to make a little tap on each as he passes to gauge the volume of ‘angels share’ taken. A curious noise, but strangely compelling, as if each barrel were alive; perhaps to Tommaso they are. He listens to them, and at night can often be found pacing the aisles hearing the creaks and groans as the barrels flex with the contents inside.

Sand is everywhere on the floor and blown onto of the top of the barrels themselves like a coating of golden sugar. The place is reminiscent of an untouched museum, which it could be argued the Florio cellars are.

“The sea and the season are important for ageing, the aromas of the sea and the town come into the winery to improve the aromas of the final marsala,” Tommaso says.

Some barrels are so old it’s hard to believe they can still be used, but any cracks or fissures are healed by the Marsala inside, as escaping tears of wine crystalize, stopping further seepage. With some barrels becoming too old (over one hundred years in some cases), new ones enter the winery, on average 30 new barriques a year.

The many styles of Marsala

I asked Tommaso if he would like to expand his work and cellars? “At the moment we have six million litres, and this is a lot of work, so perhaps no expansion yet!”

However, Florio is looking to build a new room just to age spirits from producers keen to finish their whisky or rum in their famous Marsala barrels. Such collaborations help to make Florio stay relevant in an often-aggressive drinks industry. Competition is an age-old problem for a wine style that given its high alcohol content remains distinctly unfashionable amongst some consumers.

However, lovers of Italian wines and history can’t fail to be moved by the charms not only of the wine cellars themselves, but also of the complexity of the palate.

We were treated to a range of styles from the dry Vergine Riserva (less than 4% residual sugar and aged at least 10 years) to the sweeter Semisecco wines (70g/l of sugar). When eaten with traditional antipasti fayre it’s hard to believe these wines aren’t enjoyed more often. A great talking point as each bottle now shows a unique map, giving the consumer the exact location of the barrel from which their bottle was drawn.

Before we left, Tommaso had one last surprise. Drawing off a sample from a vintage which we have been asked not to share, such was its rarity. The liquid was almost liquorice in color, perhaps one of the most complex and pronounced wines I’ve ever been lucky enough to taste. Older than me by a margin, it was a rare treat to taste such a special Marsala alongside one of the wine world’s most important figures, Tommaso Maggio.

So, the next time you think that Marsala should be reserved for your tiramisu, spare a thought for the guardians of these magical wines. Savor a glass of something sensational just to celebrate the artistry of Marsala wine itself. Cheers.